Scene of the Crime in Missing Girls: In Truth Is Justice

Sunday’s issue of the NY Times

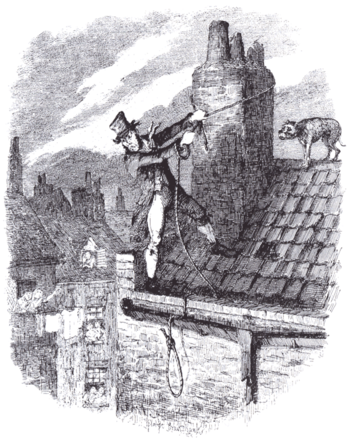

includes an article by Nicholas Noyes which visits (in a sense) the subject of this post. It’s named How to use a Novel as a Guidepost (1/15/17). He begins by quoting from Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist: “It was nearly eleven o’clock when they reached the turnpike at Islington. They crossed from the angel into St. John’s Road; struck down the small street which terminates at Sadler’s Wells Theatre…”

It is at this point that Noyes has me body and soul. Why? Because I love the the idea that you can literally walk the route, take the steps, that the characters in a novel have taken. Dickens takes his characters around a real landscape. The technique lends a feeling of reality to the narrative that’s hard to achieve any other way. I love weaving reality into fiction, and laying out the exact geography that’s trace-able by the reader who wants to break out a map or actually go to the spot.

Of course, in a novel the characters aren’t usually real. But the geography of the story can be precisely so. Noyes provides a map and illustrations. But this was from a hundred or more years ago, you may say. You can’t actually trace the steps. Oh, but you can, as Noyes goes on to show.

And so we come to the “true crime” aspect of this post.

I have published a novel Missing Girls: In Truth Is Justice in which a fictional girl is abducted and the parents traumatized by their inability to do anything about it—until they stumble into an intersection with a true crime that surprisingly provides them a path to pursue. It is the somewhat famous Edgar Smith case from 1957 in New Jersey.

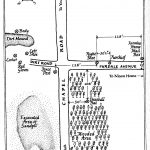

It turns out there is a wealth of information and detail about the crime available for research. You can go to the scene and see for yourself where it all transpired, using the novel as a guidepost. And if you ever doubted that Smith was guilty of murder, you can clearly see for yourself by exploring the geography that is still possible to trace. There’s something fulfilling about proving things through the truth of time and space.

There are maps and transcripts…

So you go there, and you drive the roads. You see how time has changed the landscape. A key aspect of the Edgar Smith murder trial hinged on the jury believing that Smith’s friend could have been at the scene of the crime when he said he was. The friend claimed to be making a drug store package delivery at the time. So you check it out for yourself. You time how long it takes to deliver such a package and get back to the starting point (even if it’s just online in Google Maps). For yourself. Then you know the incontrovertible proof and the truth.

The novel encompasses much more than just the story of Edgar Smith’s crime. Arriving at the the truth of the crime intersects and spills over the primary plot line by providing the mother a way to escape a suffocating inability to help find her missing child. At the same time, it lends a feeling of truth and reality to the fictional abduction.

What are your thoughts about truth and reality as they pertain to your writing? Would inclusion of real places add anything to your stories?